German authorities urged to investigate top three meat companies over human rights risks in Brazil

Link to Report in English Link to Report in German

- New research suggests soy used to feed German pork and poultry has high risk of exposure to human rights violations and deforestation in Brazil

- Legal experts say market incumbents may be in breach of the law for failure to interrogate these risks

Germany’s trade agency (BAFA) is being urged to investigate three of the country’s biggest meat producers, as new research indicates that the soy used to feed their livestock is exposed to a high risk of human rights abuses and deforestation in Brazil.

NGOs ClientEarth, Deutsche Umwelthilfe (DUH) and Mighty Earth have written to Germany’s Federal Office of Economic Affairs and Export Control (BAFA), saying that there is scant evidence that these risks are being properly addressed. Inadequate due diligence in light of these risks would put pork giants Tönnies and Westfleisch, and major poultry producer Rothkötter, in breach of Germany’s new Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (LkSG). The NGOs are pushing the agency to investigate.

The submission presents BAFA with new research from DUH and Mighty Earth, which tracks soy from the Brazilian Cerrado, where human rights abuses are rampant, via the Netherlands, to soy terminals in Germany, and ultimately to Germany’s biggest animal feed facilities, farm suppliers and slaughterhouses.

The findings suggest a link between the three companies and cases of rights violations and deforestation in the Cerrado savannah – in particular through likely connections to Bunge, one of the world’s biggest soy traders, which exports hundreds of thousands of tonnes of soy from the Cerrado to Germany each year and has an alarming track record when it comes to deforestation links.

According to the NGOs, the likelihood of the soy being contaminated is strong enough to warrant thorough interrogation by the companies. Despite some claims regarding deforestation from Tönnies, and generic statements on human rights from each company, the NGOs argue that there is reason to doubt that appropriate steps are being taken.

Under Germany’s supply chain law, in force since January 2023, this potential exposure to human rights risks in the companies’ supply chains should be addressed through appropriate due diligence measures – soy industry ‘sustainability’ certificates relied on in the past alone are no longer acceptable.

The groups claim this also leaves Germany’s major supermarkets, like Aldi, Lidl and Edeka, at risk of selling pork and poultry products with serious rights issues attached – and the meat companies open to legal sanction.

ClientEarth law and policy advisor Kaja Blumtritt said:

“Given the wealth of information about the environmental and human rights risks associated with Brazilian soy, meat companies should be taking urgent action to ensure that they are not contributing to land-grabbing, displacement of communities, deforestation and wider ecosystem destruction through their soy supply chains.

“We don’t see real evidence of this happening in the case of these three companies – despite compelling and growing evidence of risk factors. This kind of failure would amount to a breach of the law – that’s why we’re asking the enforcement authority to step in and dig deeper.

“We’re looking at a new era when it comes to supply chains. Supply chain laws should prompt proper interrogation of possible risks – boilerplate text does not constitute compliance. With new laws in force, and ever more evidence of why we need them, companies need to be thinking at a new level when it comes to transparency and accountability.”

DUH and Mighty Earth’s new report traces ever stronger links between soy that feeds German livestock and major problem areas in the Brazilian Cerrado – a vast and invaluable tropical savannah and Brazil’s biggest ecosystem after the Amazon rainforest, home to 5% of the world’s biodiversity, and the supplier of water to eight out of 12 of Brazil’s river basins.

In DUH and Mighty Earth’s report, Brazilian NGO and report collaborator Instituto Sociedade, População et Natureza is quoted as saying:

“We are horrified, witnessing how the industrial soy production for export, including to Europe, is expanding like an uncontrollable cancer in the Cerrado. Nature, biodiversity and people are being ruthlessly sacrificed for consumption of the Global North.”

Soy production in the Cerrado is notorious for its established links to human rights violations and environmental destruction – impacting local, traditional and Indigenous communities in particular. Nearly half of the Cerrado has already been razed to make way for industrial agriculture. Land-grabbing – the theft of Indigenous, local and traditional lands – to make way for industrial soy operations is a well-known and widespread problem. Meanwhile, life for those who have been able to stay on their land is challenging: large-scale pesticide use threatens ecosystems and human health – and soy monocultures are attracting pests that disturb local farming. And the intense water use required for industrial soy production, combined with rampant deforestation and its effect on rainfall, is resulting in drier lands, more forest fires and more sustained drought.

The destruction in the Cerrado is, conversely, detrimental to soy yields. Data shows that disruptions to rainfall, higher temperatures and strained soils have lowered production in intensively farmed areas in the Amazon and Cerrado by up to 12%. This plays into a wider issue that too many companies are not addressing yet: biodiversity loss as a material financial risk.

DUH CEO Sascha Müller-Kraenner said:

“DUH and other organisations took a closer look at the risks posed by the agricultural production in the immensely important ecosystem of the Cerrado and its people and showed the ties to the German pork producers Tönnies and Westfleisch. These companies need to create transparency in their soy supply chains to safely exclude environmental destruction and human rights violations. They must respect human rights, exclude problematic suppliers, and use advanced monitoring systems to guarantee transparency and adherence to sustainability standards. Shifting the responsibility onto livestock farmers is not an option.”

Alex Wijeratna, Senior Director at Mighty Earth, said:

“Mighty Earth and many others have warned of the devastating impact of soy expansion on Indigenous communities, ecosystems and wildlife in Brazil’s threatened Cerrado savannah. This unique landscape is disappearing three times as fast as its neighbour the Amazon, taken by agriculture with soy giant Bunge on the frontline of this destruction. German meat giants Rothkötter, Tönnies and Westfleisch likely links to Bunge soy suggests they have little regard for people and planet, given Bunge’s known links to land grabbing and deforestation in their Cerrado supply chain. We hope a BAFA investigation to see if they’re breaking German law will focus their minds.”

ENDS

Notes to editors

About the companies

Rothkötter is a German-based supplier of poultry feed and meat, with an annual turnover of €1.5 million. Tönnies and Westfleisch are German slaughter and processing companies, with annual turnovers of €6.8 billion and €3.35 billion respectively.

Tönnies claims that most of its feed has been deforestation-free since the start of 2024 – and that all of it will be by the end of 2025. The other organisations in question do not seem to have a similar commitment.

Bunge is one of the ‘big four’ agricultural commodity giants, also known as the ‘ABCDs’ (Archer Daniels, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus). Headquartered in Switzerland, its 2023 revenue was over €53 billion. Bunge is one of the largest soy exporters from Brazil and one of the largest importers of Brazilian soy in Europe. Its supply chain has been consistently linked with suspected instances of deforestation and human rights violations such as land-grabbing. See information also from Friends of the Earth and Global Witness. Compiled, a solid body of research points to a significant risk that Bunge’s supply chain would contain tainted soy.

Bunge has a stated global commitment to rule out deforestation from its supply chain by next year – but just this month, it was reported that one of the corporation’s suppliers had been issued with a fine of nearly $1 million for sourcing soy from illegally deforested land in Piuai in the Cerrado. The land in question – 2,500 football fields’ worth – was supposed to be off-limits to deforestation and agriculture, yet appeared to have been used to mass-cultivate soy anyway.

See Mighty Earth’s previous report on Bunge: Saving the Cerrado: Why Bunge, governments and supermarkets must act fast (2023)

About the new DUH and Mighty Earth report

Key findings:

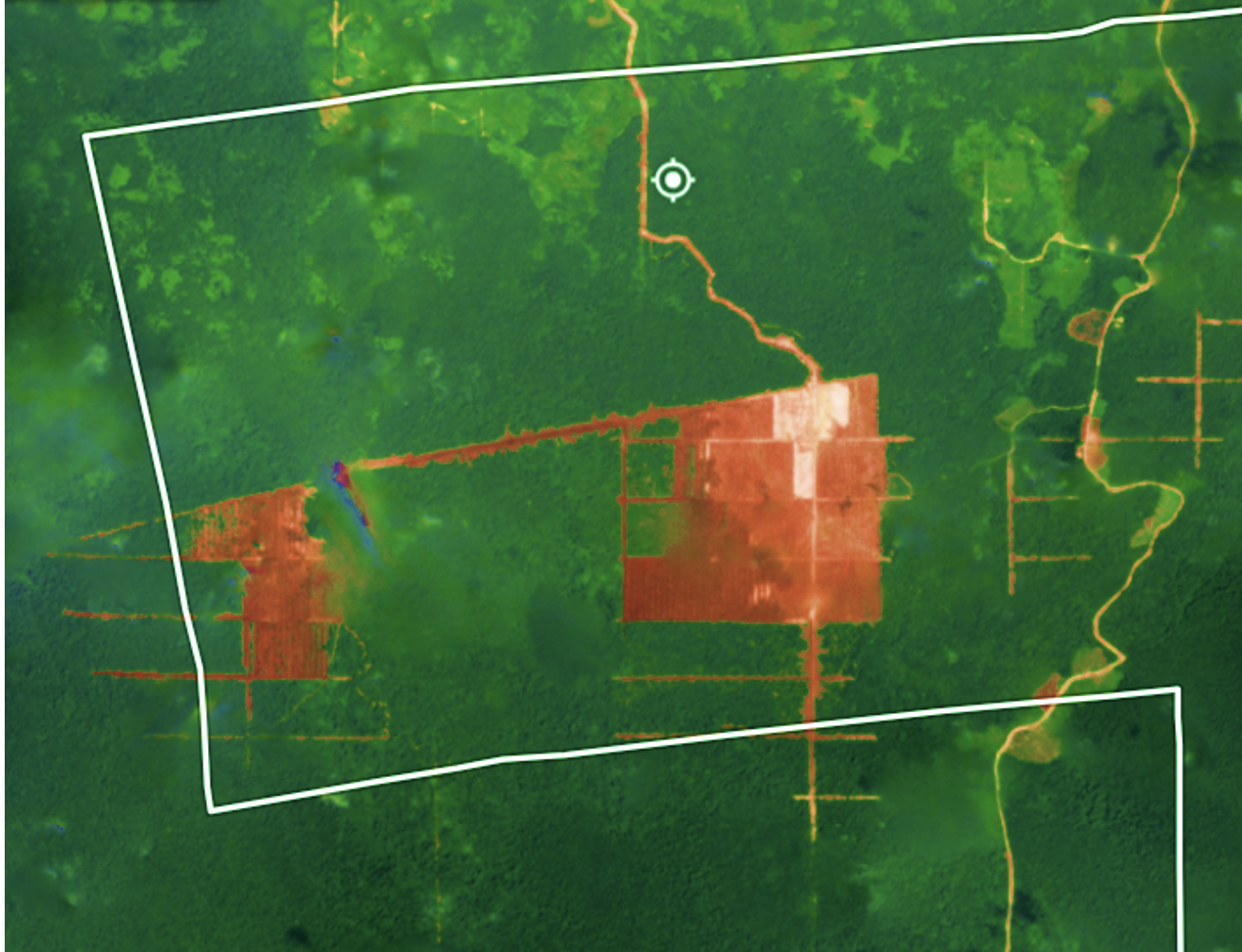

Investigators traced ship movements from soy ports in Brazil – including soy from high-risk areas in the Cerrado – to Bunge and its soy silos in Amsterdam, Netherlands. Further analysis showed soy then moving to supply feed producers in the Oldenburg-Münsterland and Weser-Emsland regions in Germany.

Interviews with animal farmers confirmed that they had bought feed from producers that buy Bunge soy – then their animals were delivered to the slaughterhouses of Tönnies and Westfleisch.

Findings about Rothkötter are principally from Mighty Earth’s 2023 report (linked above).

What is ‘supply chain segregation’

To ensure that soy and other commodities are not ‘tainted’ either with products that have been sourced from illegally deforested land or are linked to human rights violations, or products whose origin is unknown, it is important that ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ supply chains can be kept separate via individual storage and handling facilities – this is known as ‘segregation’. This means that safeguards are put in place to guarantee that soy from known and sustainable sources is kept physically separate from soy from other sources.

However, in practice, there is no guarantee that this happens.

How much soy is used in animal feed?

More than 75% of global soy harvest is used in livestock feed.

Feed supplemented with soy contributes to a high growth rate – accelerating animals’ journey to market, and reducing the amount of time they spend in rearing facilities. Pigs in industrial rearing facilities can gain nearly 1kg in weight each day. Soymeal constitutes an estimated 9% of pig feed and around 26% of chicken feed.

Imported soy is currently seen as a highly cost-effective feed for an industry under financial strain. 740,000 tonnes of soy was fed to pigs in Germany in 2023. [1]

How much Brazilian soy does Germany import?

In 2022, Germany imported around 2.3 million tonnes of soymeal. Around 50% came from Brazil (Mighty Earth – Rapid Response).

According to Trase, more than half of the soy imported by Germany from Brazil in 2020 came from the Cerrado. However, soy trade flows can be difficult to trace. Import figures are likely to be higher if indirect import flows through other EU Member States to Germany are taken into account – and nearly 30% of Brazilian soy imported directly to Germany can’t be traced back to a specific biome.

About the German Supply Chain Due Diligence law and the legal procedure

The Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control (BAFA) is the Federal agency responsible for enforcing Germany’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Law (Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz (LkSG)). The NGOs are calling on the agency to investigate their concerns of non-compliance with this law.

The supply chain law requires German companies to investigate potential human rights and environmental risks arising from the span of activities in their value chain – in Germany and abroad – that enable their business to operate. In the case of German meat producers, this includes the production of the soy in Brazil that is used to fatten the millions of pigs and chickens slaughtered every year in Germany.

Under the LkSG, the three target companies are obliged to carry out a risk analysis to identify relevant human rights risks (§5) at its direct suppliers and take corresponding preventive measures (§6) and remedial action (§7). These due diligence obligations extend to indirect suppliers on an ad-hoc basis where the company has actual indications that human rights violations at indirect suppliers appear possible (§9(3)). In Tönnies’ and Westfleisch’s human rights declarations, required under the law, none of the obvious risks related to soy (deforestation, land rights, health impacts from pesticides) are cited in relation to soy in their supply chains. ClientEarth believes this indicates non-compliance with basic formal requirements of the law. Rothkötter mentions some relevant risks but predominantly contains broad-spectrum statements and vague commitments. There is no publicly available information that would show that the company is thoroughly interrogating soy-related human rights risks, nor that it is implementing appropriate due diligence measures with regard to these risks.

As stated in DUH’s joint report: “In our view, the due diligence standards for indirect suppliers must be applied to the companies covered in this report, as there are factual indications of human rights or environmental risks that activate the company’s obligations.”

Non-profit legal group ClientEarth raised these concerns with the companies earlier this year in written letters, flagging that they may be in breach of their legal obligations under the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act. Their responses failed to convince the legal non-profit that they were taking adequate measures to comply with their legal obligations and minimise the risk that their supply chains were connected to serious human rights and environmental violations in the soy fields of Brazil.

Following the launch of the new report, “Soy Story”, ClientEarth, DUH and Mighty Earth have written to Germany’s economic affairs and export agency, the enforcer of the supply chain law, to request it investigate the situation.

Other legal procedures relating to soy supply chain risks

ClientEarth filed an OECD complaint against Cargill in the US in 2023 over concerns about possible ‘dirty’ soy in the company’s supply chain, and similarly inadequate action to rule it out. There has been no formal update as yet.

Footnotes

[1] 8.21 million tonnes of compound feed was fed to pigs in Germany, according to Federal figures. Profundo estimates 9% of the compound feed is soy – leading to an estimate of 740,000 tonnes.

About Mighty Earth

Mighty Earth is a global advocacy organisation working to defend a living planet. Our goal is to protect half of Earth for Nature and secure a climate that allows life to flourish. We have achieved transformative change by persuading leading industries to dramatically reduce deforestation and climate pollution throughout their global supply chains while improving livelihoods for Indigenous and local communities across the tropics. www.mightyearth.org

About Deutsche Umwelthilfe

Environmental Action Germany (Deutsche Umwelthilfe e.V. – DUH) was founded in 1975. The organisation is politically independent, recognised as a non-profit organisation, entitled to bring legal action and it campaigns mainly on a national and European level. Environmental Action Germany supports all sustainable ways of life and economic systems that respect ecological boundaries. At the same time, the organisation fights for the preservation of biological diversity and the protection of natural assets as well as for climate protection. The organisation is convinced that only energy supplies based on efficiency and regenerative energies, sustainable mobility, the respectful handling of our natural resources and the avoidance of waste will secure life on our planet.

About ClientEarth

ClientEarth is a non-profit organisation that uses the law to create systemic change that protects the Earth for – and with – its inhabitants. We are tackling climate change, protecting nature and stopping pollution, with partners and citizens around the globe. We hold industry and governments to account, and defend everyone’s right to a healthy world. From our offices in Europe, Asia and the USA we shape, implement and enforce the law, to build a future for our planet in which people and nature can thrive together.