Sourcing Responsible Nickel for EVs

Update, 10-Nov-2023: Civil society coalition urges President Biden to think twice about a Critical Minerals Agreement with Indonesia. Read our latest report, coalition letter, blog post, and press release.

Electric vehicles (EVs) are vital to the transition away from fossil fuels toward clean transportation. They reduce air pollution and are more efficient than cars that run on gasoline. Even better, their climate benefits increase as we green the rest of the electric grid.

EVs will help stop the worst of the climate crisis – if we can find a better way to build them. But sourcing minerals that are needed to run EVs in a responsible manner has proven to be a challenge.

Nickel Mining for EVs in Indonesia

Batteries with high amounts of nickel enable EV’s to travel farther distances. Indonesia currently supplies half of the world’s nickel. As this share grows, the Indonesian government is betting big on the industry and supporting a huge buildout of captive coal plants. Companies are responding to increased demand for nickel and other extractives by resorting to mining operations that damage fragile ecosystems, create toxic waste, and pollute the climate. Coverage from the Financial Times featuring Mighty Earth’s work with our partners Brown Brothers Energy and Environment expands on how Indonesian forests are being devastated by nickel demand (pictured below).

To better understand the impacts of nickel mining to supply EVs that are sold to customers around the world, we investigated 329 nickel mining concessions, i.e., areas allocated by the government to companies to exploit, across Indonesia and found that close to 80,000 hectares of forest have already been cleared to extract nickel ore. This is likely an underestimate. Worryingly, more than half a million additional hectares of Indonesian nickel concessions that are still forested, but not yet cleared, are under threat.

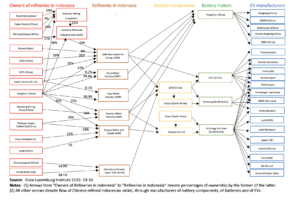

Figure 1: Nickel mined in Indonesia makes its way into the batteries of American, European and Chinese made electric vehicles

For each of the 329 concessions we evaluated, we used government license documentation and ownership profiles to determine a minimum timeframe for how long each mine has been in operation. Next, we used deforestation alerts and satellite imagery to confirm with a high degree of certainty that land clearance within the concession boundaries was specifically to mine nickel. At a minimum, over 76,031 hectares of forest have been lost across nickel mining concessions in Indonesia since the concessions were granted for nickel mining. That said, many of the highest deforesting mines were clearing forest well before this timeframe. Zooming out, an estimated 153,364 hectares of deforestation have occurred within the boundaries of Indonesia’s 329 nickel concessions since the year 2000. The true impact of Indonesia’s nickel mining over the past two decades is likely somewhere in between the minimum deforestation of 76,031 hectares and the total deforestation of 153,364 hectares.

Of the 329 Indonesian Nickel concessions we evaluated, we looked in further detail at 25 mines that pose the greatest threat to forests:

Figure 2: 25 of the top Indonesian nickel mining concessions leading the destruction of natural forests

“High Carbon Stock”* forests have large amounts of carbon contained in the forest and soil, important to storing carbon that would otherwise be in the atmosphere. They range from intact old growth forest to young regenerating forests which, if left alone, will easily recover. Out of the 25 concessions above, 9 contain significant amounts of High Carbon Stock forest, (75% or more). Another 9 concessions are under 50% HCS, indicating that there may be degraded land in these concessions that could be mined for nickel. “Key Biodiversity Area”** are critical habitats where many different plants and animals reside; biodiversity in intact landscapes allows ecosystems to thrive. Of the 25 concessions we looked at, 44% contain Key Biodiversity Areas.

Runaway Buildout of Coal Plants

Indonesia is seeing a huge build out of captive coal plants to power nickel smelters. As of the end of 2022, the country had 15 nickel smelters and plans to build at least six more. Coal capacity of the Morawali Industrial Park (IMIP) alone will have 5 GW of generating capacity from coal-fired plants – or as much capacity as the whole of Mexico or Pakistan. Weda Bay (IWIP) has plans will provide an estimated 3.78 gigawatts per year of coal energy, which is more coal than Spain or Brazil use in a single year. The vast majority of these plants will use low quality coal from Borneo. Continued reliance on of coal to power the nickel industry will perpetuate Indonesia’s role as one of the world’s biggest emitters- putting Indonesia on the path to be the 6th highest climate polluting country in the world.

Harm to Forests, Animals, and Oceans

Nickel is primarily found in an area of Indonesia teaming with wildlife. Sulawesi and Malaku lie in the transitionary zone between Asian and Australian plants and animals. Like the Galapagos, it has been called a “living laboratory of evolution.” It is home to a dizzying array of species, some of which are found nowhere else in the world. Offshore, some 30% of the world’s precious coral reefs exist. By destroying forests and polluting the ocean, mining companies are also destroying the diversity of plants and animals in the area. Deforestation and biodiversity loss lessen the forest’s ability to store carbon that would otherwise contribute to the climate crisis.

Bintang Delapan Mineral

Bintang Delapan Mineral is in the eastern side of Central Sulawesi, just inland from one of Indonesia’s main nickel processing sites, Morawali Industrial Park. Bintang Delapan, together with Chinese nickel refining giant Tsingshan, owns more than three quarters of Morawali Indistrial Park.

Roughly 85% of the concession is covered with High Carbon Stock forest. The High Carbon Stock approach was developed to identify forest areas and the degraded land with low carbon and biodiversity values that may be developed. Even more concerning, 17,105 hectares of Bintang Delapan, almost the entire area of the concession, is located within an area classified by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature as a “Key Biodiversity Area.” Already 2,738 hectares have been cleared within the concession since the date of its license adjustment in 2010.

Figure 3: Deforestation alerts within Bintang Delapan concession boundary, much of wish is classified as Key Biodiversity Area.

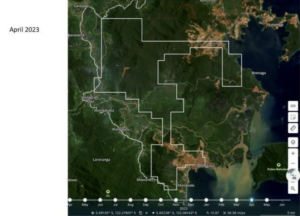

Aneka Tambang

The maps below show the largest nickel mining block of state owned miner Aneka Tambang, located in Southeast Sulawesi. It is roughly 60% High Carbon Stock Forest. Already 2,776 hectares have been cleared since 2013. Looking at the concession in 2017 and again in 2023, mining within 100 meters of the ocean is more visible and the disgorging of sediments into the ocean are visible from the satellite imagery. In addition, the river running through the Aneka Tambang concession is visibly loaded with sediments. Four additional mines out the 25 we examined in detail have also cleared forests within 100 meters of the ocean.

What Can be Done?

The goal is not to stop electric vehicles from being made, but to ensure that forests, ecosystems, and local peoples are protected as we make the transition. One of the most effective potential solutions lies in building traceability and transparency into supply chains.

Increasing traceability means that companies track where the minerals come from, from the mine to the refinery, to the processers, to the manufacturers using nickel in their car batteries. Transparency means making this supply chain public, allowing consumers and civil society to follow the supply chain of nickel. All companies involved in the EV supply chain, including auto manufacturers, can start to minimize harm by ensuring that the nickel that they use is not sourced from mines in key wildlife habitats or other High Conservation Value (HCV) areas.

Transforming the nickel industry is no small task, but it is possible. In Southeast Asia, deforestation in the palm oil industry has decreased by 90%, thanks to policies and enforcement mechanisms that protect forests and animals in the area. The nickel industry can follow suit by increasing traceability and transparency, and supporting policies that protect forests, communities, and wildlife. By doing this, they can practice responsible extraction while continuing to grow the EV industry—building a cleaner and healthier future for the transportation sector and the Earth as a whole.