Can Agroforestry Provide a Lifeline for Struggling Rubber Farmers and Threatened Forests?

Rubber trees in Hat Yai, Thailand, Photo by Wutiporn Pakdi (นายวุฒิพร ภักดี)

Climate disruption: an existential threat for smallholder farmers

Amidst the horror and uncertainty of a pandemic, the climate disaster is still unfolding and it effects are being felt around the world.

Climate change is happening, and its impacts are experienced around the world at various tempos. The frequency and intensity of fires, severe storms, heat waves, and floods are accelerating. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center tweeted that “…every month of 2020 has either been the warmest or second warmest on record across the globe.” This faceless menace of climate change has become a personal threat to people living in vulnerable front-line communities disproportionately burdened with its impacts on their livelihoods and well-being.

Perhaps foremost amongst these often-forgotten individuals at the sharp end of a changing climate are small family farmers, or smallholders. For them, agriculture is not only their main source of income, but also of their food security. As a warming atmosphere intensifies the world’s weather patterns, it also wreaks havoc on soils and crops, creating a truly existential crisis for millions of smallholder households around the world who rely on their environments to make a living.

One part of the world where this threat is exemplified is in the Greater Mekong; a region that includes southern China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. For millions of smallholders in this region, changing climatic patterns are profoundly impacting the cultivation of traditional food and cash crops, to the extent that their very viability is at stake.

Risky rubber

Among the most threatened of these cash crops is natural rubber, which is derived from latex tapped from the tree species Hevea brasiliensis. Rubber farmers produce around eighty-five percent of the world’s natural rubber through their small, family-run enterprises whose land holdings commonly cover no more than a few hectares, with the rest grown on industrial plantations.(i) Around ninety percent of rubber is grown in Asia, with an increasing amount coming from the Mekong region. Only until recently, World Agroforestry reported rubber as the most rapidly expanding tree crops within mainland Southeast Asia.(ii) Farmers and their families in the region face the brunt of human-induced climate disruption because they depend directly on the environment for their survival. Many will suffer through heat, floods and corrupt government policies and unfair industry practices, while others will feel compelled to change their crop completely or leave the land altogether to swell ranks of the region’s already overburdened mega-cities.

An Eco-Business article covered the climate change impacts Dr. Sara Bumrungsri, a rubber farmer and researcher, experienced on his land. He reported that, “In the last few years in southern Thailand, we have had no rain for 90 days. I have seen young rubber trees and trees that are over 10 years old dying.” Intensifying wet and dry spells are destructive to farmers’ livelihoods; Dr. Bumrungsri observed that 5 percent of rubber trees in Southern Thailand have died, consequently leading to farmers producing less yields and receiving significantly less income.(iii) These vulnerabilities are compounded by the rubber sector being affected by a 40% drop in global prices since 2016, as well as quarantines and other restrictions during Covid-19 more recently. (iv) The projected losses in production also threaten the global natural rubber value chain. This includes but is not limited to the automobile and medical supply industries, which are facing supply shortages and are key in producing vehicle tires and latex gloves from this raw material. Yet, while large global companies can absorb these economic shocks, smallholder households are much less able to do so.

Agroforestry: a pathway to resilience

In order to survive, the agricultural practices adopted by smallholder rubber producers in the Mekong region (and beyond) will need to become resilient to climate change. Rather than dealing with droughts and floods as they come, farmers may now have to respond to climatic changes proactively, in ways that will alter the way they farm irrevocably. Farmers urgently need innovations that will allow them to produce enough to support themselves and provide industry with a sustainable supply of agricultural raw materials for an ever-growing global demand of products.

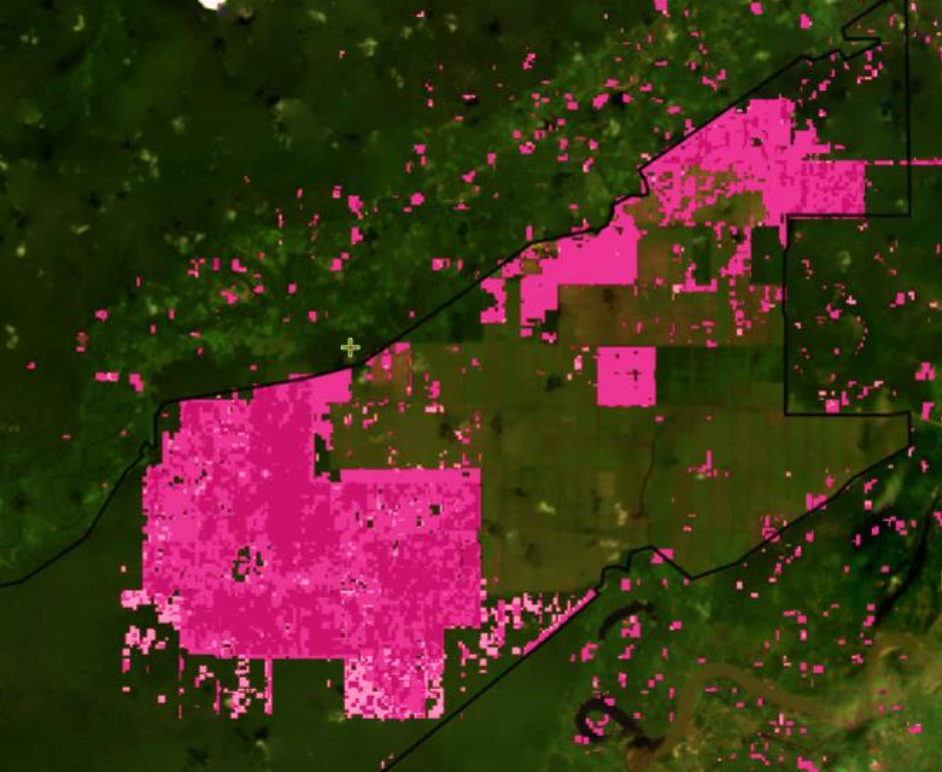

As demand and interest grows in sustainable natural rubber, Mighty Earth, is working hard to ensure there are industry-wide solutions that can help to reduce and eliminate deforestation – a direct contributor to climate change – while enhancing the livelihoods of rubber farmers along these supply chains.

One such solution – or rather, set of solutions – are agroforestry systems. Put simply, agroforestry involves the cultivation of trees alongside other crops, or with livestock. There are numerous different types of agroforestry systems, which provide an array of agroecological benefits. Agroforestry commonly increases on-farm biodiversity, strengthens soil composition, provides microclimatic control, and reduces damage from pests and diseases that attack crops, including those that affect tree crops such as rubber. Because they more closely mimic natural ecosystems – and because they tend to be more effective at protecting soil structure and moisture retention – agroforestry systems also tend to be more resilient to extreme weather events.

Rubber Agroforestry Farm in Thailand, Photo by Mighty Earth

Agroforestry also has important socioeconomic benefits. Long before monoculture practices replaced traditional rubber cultivation systems, integrated farming methods provided both an environmental and economic opportunity for smallholders; cultivating multiple crops alongside rubber trees allowed for more sources of income and higher land productivity. Smallholder farmers, most of whom live with a high degree of financial uncertainty, can diversify their household incomes from agroforestry by diversifying their products.(v) This spreads risk temporally across seasons and reduces reliance on income from a single commodity – a critical benefit in the case of rubber, which goes through cycles of price peaks and troughs. The rediscovery of these traditional principles, coupled with the application of scientific understandings of how different tree-crop (and tree-livestock) create particular agroecological synergies, means that agroforestry is now undergoing a resurgence of interest, in an era when its benefits may be most keenly felt.

Smallholders cannot do this alone. In order to secure rubber farmers labour rights and livelihoods when shifting from monoculture towards a more sustainable integrative farming method, financial and technical support is needed. Other stakeholders, such as governments and rubber-dependent firms can support farmers by adopting sustainability policies and actively implementing them by supporting farmers and the uptake of agroforestry as a solution. Further, governments can create clearer language to secure the land tenure rights of smallholders which will encourage and enable farmers to adopt more long-term sustainability initiatives, like agroforestry, on their own.

The Global Platform for Sustainable Natural Rubber (GPSNR) was established to develop and maintain sustainable natural rubber standards in the industry. Among the platform’s list of stakeholders are the world’s largest tire companies, rubber manufacturers and processors, and other users who ultimately have the most power in driving the direction of whether natural rubber production standards will remain stagnant or more towards truly sustainable and ethical solutions that will benefit the entire value chain. Agroforestry is more than adopting a policy: It’s an ethos that encourages a climate-resilient, socially equitable supply chain. If GPSNR and other multi–stakeholder platforms are promoting to protect ecosystems and human rights, then advocating for those heavily affected by climate change – particularly farmers- must become a more urgent priority.

The time is now for farmers and industries to work together to reduce irreversible risks and losses set by climate change. Agroforestry is a step closer to a sustainable transformation in the natural rubber sector.

Sources

(i) Zengkun, F. (2020, April 15). Smallholder farmers: If you want to save forests, pay more for sustainable rubber. Retrieved August 18, 2020, from https://www.eco-business.com/news/smallholder-farmers-if-you-want-to-save-forests-pay-more-for-sustainable-rubber/

(ii) Chin, N. (2020, February 03). Drought, deluge, disease: How should the natural rubber industry respond to climate change? Retrieved August 18, 2020, from https://www.eco-business.com/news/drought-deluge-disease-how-should-the-natural-rubber-industry-respond-to-climate-change/

(iii) Ibid.

(iv) Addressing the Impact of COVID-19 on Natural Rubber Smallholders. (2020, April 29). Retrieved August 18, 2020, from https://gpsnr.org/news-publications/addressing-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-natural-rubber-smallholders

(v) Joshi, Laxman & Wibawa, Gede & Akiefnawati, Ratna & Mulyoutami, Elok & Wulandari, Diah & Penot, Eric. (2006). Diversified rubber agroforestry for smallholder farmers – a better alternative to monoculture.