Biden Climate Summit Requires Bold Industrial Decarbonization Plan

By Phelim Kine and Megan Larkin

U.S. President Joseph R. Biden’s virtual Earth Day Summit will commence on April 22 on a hopeful note. The European Union on April 21 struck a tentative climate accord designed to ensure that the 27-nation grouping reaches carbon neutrality by 2050. And Biden’s climate czar, John Kerry, and his Chinese counterpart, Xie Zenhua, pledged on April 18 to take joint “concrete actions in the 2020s to reduce emissions aimed at keeping the Paris Agreement-aligned temperature limit within reach.”

That’s the good news.

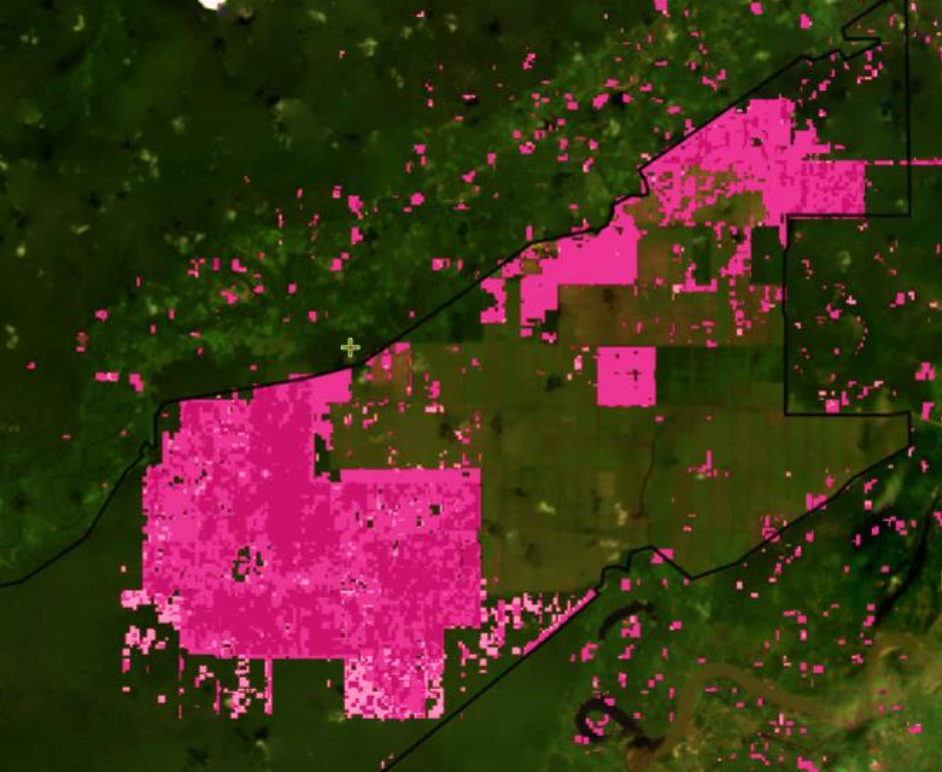

The challenge: Reaching consensus on key government priorities essential to reduce carbon emissions that are fueling the already evident negative impacts of climate change. There’s a ready short list – stopping tropical deforestation and accelerating a global transition to renewable energy. But the summit’s true success hinges on states’ concrete commitments to decarbonization of the heavy industry sector which constitutes around 18 percent of all global carbon emissions. The World Steel Institute estimates the steel sector is responsible for approximately eight percent of total global carbon emissions. The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has estimated that dramatic cuts in those emissions are essential to limit global warming to 1.5°C by 2050. The IPCC warns that failure to meet that target will greatly increase “climate-related risks to health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, human security, and economic growth.”

A growing number of the world’s largest steel companies have proactively announced that they’ll reduce their carbon emissions over the next three decades. ArcelorMittal committed on March 17 to the development and rollout of two low-carbon steel product lines including a “certified green steel” line and a low-carbon recycled steel line, respectively. Japan’s Nippon Steel has set a target of reducing its carbon emissions by 30 percent by 2030, prompting similar pledges from rivals including South Korean steelmaker POSCO and China’s state-owned Baowu Steel. And some of the world’s largest automakers are demanding that their steel suppliers provide them “green steel” car parts for their rapidly expanding lines of carbon neutral electrical vehicles.

Those corporate commitments are laudable. But decarbonizing the world’s heavy industry sector, starting with steel, is a nonstarter unless governments back up the private sector’s best intentions toward decarbonization with funding and supportive policy and regulatory initiatives. Pilot carbon reduction projects by ArcelorMittal, Tata Steel and Swedish steelmaker SSAB have hinged on millions of Euros in government support. That funding is a fraction of what is required to transition the entire global steel sector to carbon neutral status by 2050. POSCO has underscored the financial challenge of that transition when it revealed that replacement of its nine existing high carbon emission blast furnaces with carbon-neutral facilities will cost the “equivalent to its 30-year operating profit.”

Mighty Earth and The Climate Group have collaborated to create a new international multistakeholder policy tool that provides a common playbook outlining the respective responsibilities of governments and the private sector dedicated to accelerate and scale-up the decarbonization of heavy industry, starting with steel, to align with a 1.5°C global warming trajectory. The Global Framework Principles for Decarbonizing Heavy Industry (“Framework Principles”) launched in February after a drafting process that involved close coordination with industry and policy experts across the globe. These principles constitute the first-ever publicly available global guidance for how to equitably balance economic growth with decarbonization.

The Framework Principles outline the respective roles of governments and private industry to ensure the successful decarbonization of heavy industries – including steel, cement and chemicals – through allocation of public financing for emissions reduction plans. The Framework Principles specify investment in low- and zero-carbon technologies as a top government and corporate priority to help phase out fossil fuel use in industrial processes. The United Kingdom has offered a potential model for meeting this challenge through government-corporate decarbonization partnerships by earmarking an initial US$1.4 billion over 15 years to fund such initiatives. The Framework Principles are grounded in a recognition that decarbonization efforts include biodiversity and human health protections and a commitment to a just transition to a decarbonized industrial future. The growing number of corporate endorsers include Tata Steel Ltd. and JSW cement of India, China’s Jinko Solar and the U.S.-based carbon recycling firm, LanzaTech.

Governments can also play an important role by helping to foster the development of an accepted, universal standard for low-carbon or carbon-zero “green steel.” Such standards are needed to ensure that corporate carbon neutrality commitments bridge the gap between rhetoric and reality. The ResponsibleSteel coalition, which groups a diverse array of high carbon emission corporations with nongovernmental organizations including Mighty Earth, has developed standards that extend beyond greenhouse gas emission metrics to include “a wide range of social, safety and environmental issues.”

Biden’s challenge as host of the two-day summit is to align the climate pledges of state leaders of countries home to heavily polluting heavy industry sectors, including China, Japan and India, with concrete policy initiatives that will allocate state funding to accelerate industrial decarbonization. Biden himself has pledged to put “sectoral decarbonization” at the center of his administration’s “green recovery efforts,” but failed to make it a priority of his massive infrastructure spending plans.

Biden’s not alone in that gap between rhetoric and reality. Chinese President Xi Jinping committed in September 2020 to reduce China’s carbon emissions in order to reach carbon neutral status by 2060. But despite China’s status as the world’s largest steel producer, Xi has yet to allocate the trillions of dollars at his disposal via state-owned commercial banks to put wheels on that pledge. Likewise, Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga has publicly committed to transition Japan to a decarbonized, zero-emission industrial production model by 2050. But Suga’s failure to date to provide a substantive road map to that target has prompted skepticism in Japan’s business community. A survey of more than 11,000 large and small Japanese firms about Suga’s carbon neutrality target revealed that only 15.8% of surveyed companies considered it “achievable.”

Most concerning is the disconnect about the essential role of state financing for industrial decarbonization in the Indian government of Prime Minister Nahrendra Modi. RK Singh, India’s Minister of Power, last month derided other countries’ carbon net zero goals as “pie in the sky.” Singh then declared that the onus for decarbonization sat squarely on developed countries by “removing more carbon to the atmosphere than they are adding.” India’s status as the world’s third-largest carbon emitter behind China and the United States makes Singh’s dismissal of his country’s industrial decarbonization obligations particularly incongruous.

There is a growing global consensus that heavy industry decarbonization is essential to avert emission-fueled climate disaster. Biden’s climate summit will demonstrate whether that consensus can produce the necessary vision and political will to make heavy industry decarbonization a reality.

Phelim Kine is the senior director Asia at the Washington, D.C.-based environmental campaign organization Mighty Earth; Megan Larkin is an Associate at Mighty Earth where she works on its heavy industry decarbonization campaign and business development