Better protecting people and forests in the race to electrify

Analysis by Mighty Earth shows that nickel is mined in valuable forest and biodiverse areas – but it doesn’t have to be

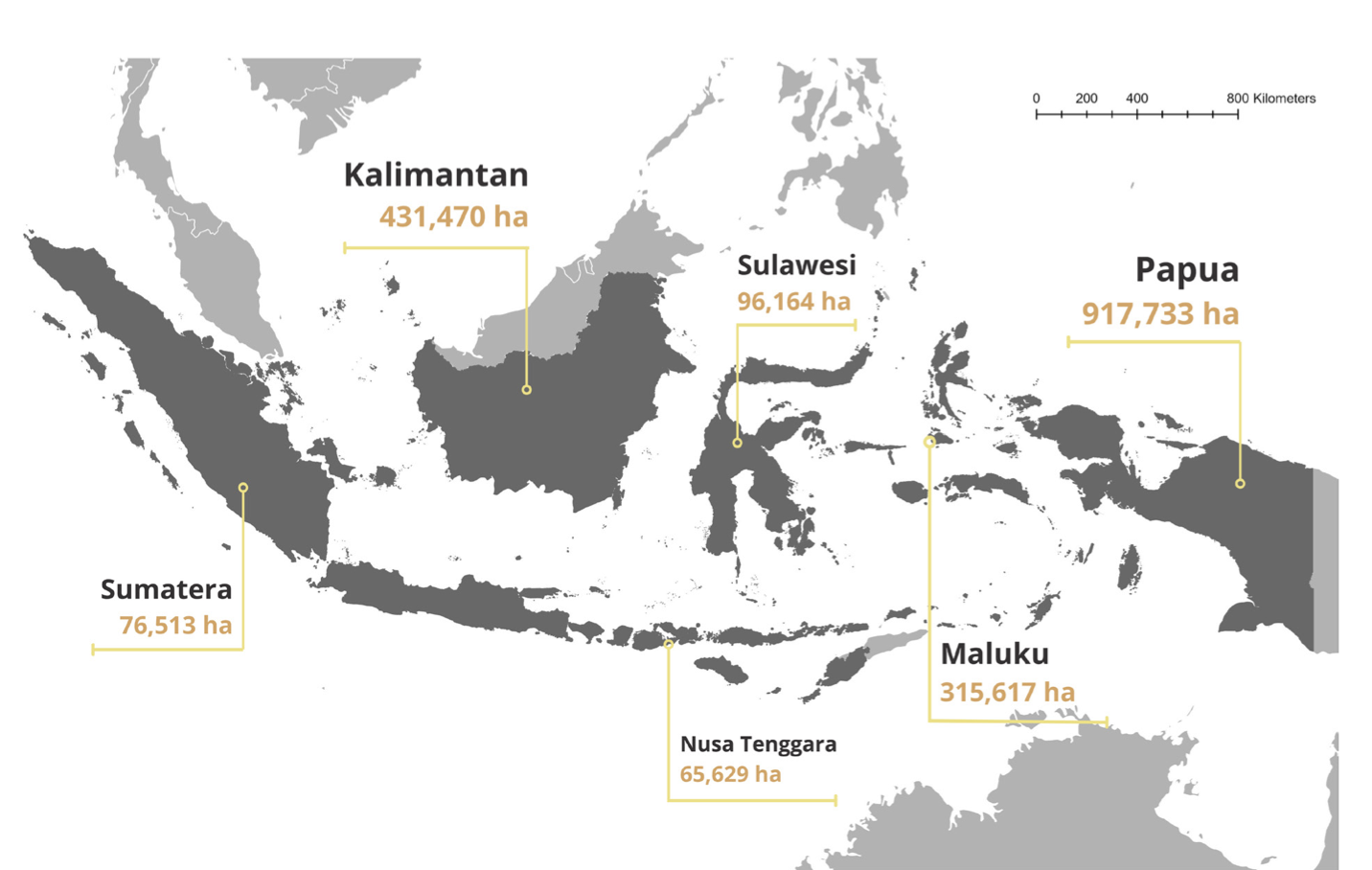

Nickel mining is driving deforestation in Indonesia, with around 80,000 hectares already cleared for nickel extraction and half a million more at risk. The rate of deforestation is accelerating as alert systems show deforestation for nickel doubling from 2020 to 2023.

Although this industry is destroying forests, nickel mining is contributing to a major solution for the climate crisis: electric vehicles. In addition to use in the steel industry, nickel is used in electric vehicle batteries, vehicles which are more efficient than gas-powered cars. As the grid is greened, their climate benefits increase. A just transition to electric vehicles is crucial. However, safeguards are necessary to ensure that electric vehicle production is in line with national and global climate commitments.

Cutting down carbon-rich trees for nickel isn’t the only way to power EVs. There could be ways to combat nickel-driven deforestation, while maintaining momentum in the transition to electric vehicles.

Mighty Earth investigated 329 nickel concessions in Indonesia listed by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources – and made our dataset publicly available here. Our findings show that the state of nickel mining in Indonesia is riddled with deforestation and questionable legal standing:

- Seventy-five concessions, or 23% of the 329 analyzed by Mighty Earth, have cleared Production Forest, i.e. land set aside for forestry uses without the legally required permit.

- At least seven nickel concessions have cleared more than Protection Forest, or land set aside to protect life and ecosystems, without the prior exemptions that would have made clearance legal.

- Twelve concessions have strip-mined within 100 meters of the ocean, a legally contested practice.

However, there may be opportunities to better site nickel mines by avoiding areas of intact forest and biodiversity hotspots. We found that:

- 1 of 5 concessions contain vast amounts of intact forest (90% or more High Carbon Stock). These areas should be avoided.

- 2 out of 5 of concessions contain smaller amounts of intact forest (33% High Carbon Stock or less), potentially providing an opportunity to mine on degraded land within these areas.

- Out of the 329 concessions in our dataset, 20 have 90% or more Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA) within their boundaries. Another 33 are 50% or more made up of Key Biodiversity Areas. These areas should be avoided, but there are nearly 275 concessions with less than 50% KBA that may provide an opportunity to mine areas without valuable biodiversity.

Each mine is responsible for getting the proper permits, conducting integrated HCS/HCV assessments where possible, and avoiding extraction on forests and Key Biodiversity Areas within their concession. Our findings aren’t prescriptive but show what might be possible: a world where we can access resources needed for climate-friendly technological advancements while avoiding carbon-rich and biodiverse areas.

Indonesia’s Role

Indonesian nickel is dominating supply chains. The country produced around 50% of all nickel used in EV batteries made in 2023. By 2029, 75% of all nickel in EVs is expected to come from Indonesia. As nickel production increases, deforestation increases.

Beyond driving this deforestation, the nickel industry is driving emissions from egregious coal usage. Indonesia has made itself a key player in the nickel industry through this huge buildout of captive coal. The country is increasing its coal capacity by at least 8 GW – the same capacity as the entire country of Pakistan. This massive buildout of captive coal allows Indonesia to produce nickel cheaply while production elsewhere in the world struggles to compete. Nickel prices may remain unstable as Indonesia continues to ramp up its production of low-cost supply, dominating the market. Furthermore, this new infrastructure for nickel processing is cementing Indonesia’s spot as one of the world’s top carbon emitters.

Illegal Clearing of Production Forest

Some forests in Indonesia are being cut down illegally for nickel mining as Production Forest is cleared without the necessary “Borrow and Use Permits” from Indonesia’s Ministry of Forestry and Environment.

Seventy-five concessions, or 23% of the 329 analyzed by Mighty Earth, have cleared Production Forest (land set aside for forestry uses) without the legally required permit.

There are many examples of mines in Indonesia operating under questionable legal conditions. In 2023, two nickel mines in South Sulawesi were accused of polluting a nearby river and allegedly operating without proper permits. One of these mines was PT Citra Lampia Mandiri, included in our dataset and imagery below, which shows that its permit partially overlaps with Production Forest. In late 2022, a provincial commission ordered the region’s environmental agency to publish the license of the two mines. The environmental agency could not publish the licenses because they had not been fully processed. Without proof of a borrow and use forest permit, a license to dump waste, and an environmental impact analysis, it suggests that the mines were operating in Production Forest without proper license. Lawyers have filed a freedom of information request for the concession’s licensing information.

In another case of questionable legaility, a Tempo investigation uncovered that several nickel companies owned by Haji Karlan in Central Sulawesi obtained authorization through inappropriate means. The letter granting a mining business license to PT Citra Teratai Indah was signed by Taslim, the Regent of Morowali. However, Taslim stated that he did not sign the letters, and the Morowali Regency Regional Secretariat’s legal division claimed that the signature was forged. The documents also had an outdated stamp (using the logo for the “Office of Energy and Mineral Resources” before its name was changed from the “Office of Mining and Energy”) which Karlan attributed to “administrative error.” According to a Pulitzer Center report, Karlan “claims that his company’s concession is located outside of the forest area, thereby he does not feel it necessary to obtain IPPKH” (a type of permit). Because of land disputes, the attorney general’s office must issue a legal opinion to allow these companies to be registered in the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources database (MODI). In other cases, provincial attorney general’s offices have issued rulings allowing 12 companies to register on MODI. Forged documents should not give license to a company to operate in Protection Forest area, and companies should not be exempt from the permitting process. Confusion, suspected bribery and illegality of this nature surround mining activity in Indonesia.

The Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry has investigated illegal mining in the past. In 2022, the ministry investigated illegal nickel mining in the Production Forest area in Lamondowo Village of the Southeast Sulawesi Province. Upon investigation, the Southeast Sulawesi regional government and police found nickel mining activity despite lack of proper permits, leading to the arrest of suspects and collection of evidence in further investigation of the case. As illegal mining is ongoing, the ministry has an opportunity to step in to investigate and enforce forestry laws.

Illegal Clearing of Protection Forest

Some of Indonesia’s nickel mines are breaking laws which prohibit mining within Protection Forests. Protection forest is land that set aside to protect life and ecosystems in Indonesia. This forest cannot be cleared without an exemption. Presidential Regulation 4 of 2004 granted five exemptions from the prohibition on strip mining Protection Forest. The five were Inco (now Vale Indonesia), two called Aneka Tambang (one in Southeast Sulawesi province the other in North Maluku province), Weda Bay Nickel and Gag Island Nickel. These exemptions have now been extended by Presidential Regulation 3 of 2023.

At least seven nickel concessions have cleared Protection Forest without the prior exemptions that would have made clearance legal (see table below).

In the case of PT Halmahera Sukses Mineral, over 260 ha of Protection Forest loss occurred. See image below for comparison of GLAD alerts in areas of Protection Forest.

Clearing In Key Biodiversity Areas and Near the Ocean

Twelve concessions have strip-mined within 100 meters of the ocean, a legally contested practice. Mining this close to the ocean is illegal only if provincial and district governments have adopted planning documents that outlaw such activities.

Runoff from mining activities have harmful impacts on nearby residents, as is the case on the island of Kabaena where a seafaring community is at risk while contaminated water cause skin lesions and prevent children from learning to swim, leading to several drownings.

Furthermore, deforestation for nickel is impacting Key Biodiversity Areas, areas with significantly biodiverse plants, animals, and habitats. Out of the 329 concessions in our dataset, 20 have 90% or more Key Biodiversity Areas within their boundaries. Another 33 are 50% or more made up of Key Biodiversity Areas.

As pictured below, Bintang Delapan concession mostly overlaps with Key Biodiversity Area.

Better Siting

Current siting of nickel mines is putting intact carbon-rich forest and Key Biodiversity Areas at risk. There are opportunities to find better places to mine nickel.

High Carbon Stock areas are defined as forests with high concentrations of carbon contained in the vegetation and soils. The High Carbon Stock Approach (HCSA) was developed to identify natural forest areas and help the palm oil sector to implement no deforestation pledges during the past decade. The HCSA helps to distinguish between viable forest areas and degraded areas. High Carbon Stock forests should be conserved due to their value as carbon stores and for their biodiversity conservation. They range from intact old growth forests to young regenerating forests which, if left alone, will easily recover.

Our findings show that 1 of 5 concessions contain vast amounts of intact forest (90% or more High Carbon Stock) – these areas should be protected. However, 2 out of 5 of concessions contain smaller amounts of intact forest (33% HCS or less)– these areas can follow the “avoid” tier of the mitigation hierarchy, providing an opportunity for mining to occur on degraded while avoiding the areas that are intact forest.

Local communities, like the people of Kabaena, are facing severe harm to their health and livelihood at the hands of the nickel industry. Implementing Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) is vital to ensure that mining is not taking place on the lands of Indigenous People or local communities.

As for coal usage, if Indonesia is to meet its climate ambitions, it must address the egregious carbon emissions of its nickel industry. Despite claims of being “environmentally friendly,” Morowali Industrial Park alone is to have 5 GW of coal-fired capacity and Weda Bay Industrial Park is soon to have a capacity of 3.5 gigawatts. With only two parks generating a combined coal capacity greater than that of entire countries, these projects are hardly friendly for the environment. Indonesian advocacy groups are pushing back on the nickel industry boom, calling for the country to stop investing in fossil fuels as one of the main contributors to the climate crisis.

We need electric vehicles to combat the climate crisis – but we can’t perpetuate the burning of coal, destruction of carbon-rich biodiverse forests or harming of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in the process. Creating environmental safeguards in the nickel industry will take strong and swift commitments from the government and the industry more broadly.

To take a deeper dive into 25 of these 329 nickel mines in Indonesia, see our paper which focuses on 25 of the top deforesting nickel mines in Indonesia.

Adhering to principles of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent is vital in any extractive industry. In the same way that mining should not take place in valuable forests and biodiverse lands, it should also not take place If traditional and customary owners of the land or nearby communities are not a free, consenting, and informed party to mining activity. For more information on how mining impacts Indigenous peoples and local communities in Indonesia, please see Climate Rights International’s report, Nickel Unearthed.