Springing into Action on Rubber

As the World Rubber Summit kicks off in Singapore, we explain why Mighty Earth has become a Founding Member of the new Global Platform on Sustainable Natural Rubber (GPSNR).

Perhaps the ‘game changer’ moment for the rubber industry came in mid-September 2016, when the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague quietly released a policy paper that seemed far removed from the dry world of natural rubber commerce.

In a shift from their traditional focus on war crimes, the ICC announced in its paper that it would start to prosecute on “crimes against humanity” resulting from large-scale environmental destruction and natural resource exploitation. This included explicit references to deforestation and the “illegal dispossession” of land, aka land-grabbing.

A complaint had recently been lodged at the ICC against the Government of Cambodia, which was accused of crimes against humanity associated with a massive wave of land grabbing over the previous decade that had led to the displacement of 770,000 Cambodians. In the vast majority of cases, local communities and indigenous peoples had been forcibly dispossessed of their traditional lands and forests in order to make way for large-scale commercial agriculture projects. The number one crop targeted for these schemes? Rubber.

The ICC’s announcement, coupled with the Cambodia case, fundamentally shifted the goalposts for rubber producers, processors, and buyers. This was no longer just about reputational risk. Chief executives of companies complicit in crimes related to environmental destruction and land grabbing could now be charged in front of a tribunal at the ICC. This was a shot across the bow of the rubber industry. Nobody wants to be in the company of war criminals such as Charles Taylor and Slobodan Milošević.

The Rubber Boom: 2000 and Beyond

Natural rubber is derived from tapping the sap (or latex) of the tree Hevea Brasiliensis, a species that grows only in the tropics. Originating in Brazil, it was introduced and propagated by the colonial powers in West Africa and Southeast Asia. Today, 90% of the world’s natural rubber comes from Asia. Most (70%) rubber is consumed by the tire industry, with other commercial uses including sports equipment, footwear, condoms, medical products and household items.

With a few exceptions, rubber has traditionally been grown mainly by smallholder farmers, or on modest estates, with a minor portion coming from large plantations either set up by the colonial administrations in African and Asian countries, or by public or private companies following independence.

However, over the past twenty years, this situation has begun to change dramatically, particularly in Southeast Asia. In countries such as Indonesia and Vietnam, commercial agribusinesses have established large numbers of new industrial rubber plantations, decreasing the share of total production by smallholder growers. Countries such as Malaysia, which already had a higher concentration of plantations, also saw the number of such large-scale operations increase significantly since the year 2000.

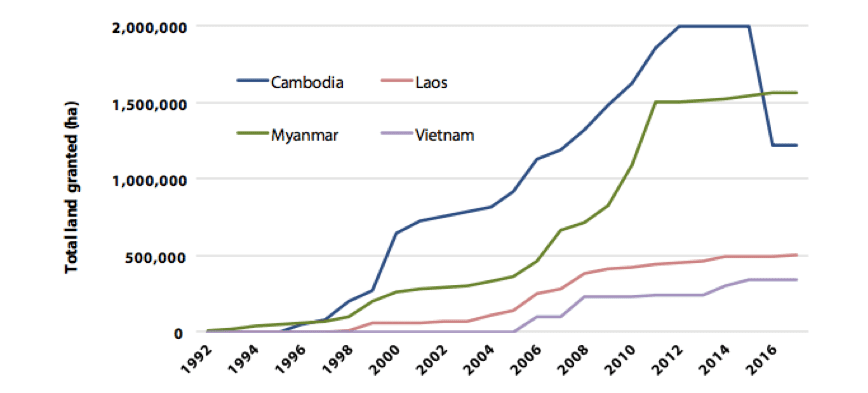

As rubber prices steadily rose in the decade between 2002-2012 (particularly in relation to other tropical agricultural commodities), commercial investors looked to open up new regions for industrial rubber cultivation: with Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar the prime targets. From around 2003 onwards, an estimated combined 1,489,500 hectares of land across these three countries was allocated for large scale rubber concessions—an area equal to the size of 19 New York Cities.

In all three countries, land for large scale commercial rubber was mostly allocated to investors based in Vietnam and China, with companies from Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Japan and Korea playing a lesser role (along with some domestic investors). In Myanmar, military-associated companies have also been major beneficiaries of land deals for rubber.

Area under agriculture and tree-crop concessions in the Mekong: 1992-2017

Source: Journal of Land Use Science, The expansion of tree-based boom crops in mainland Southeast Asia: 2001 to 2014 , Kaspar Hurni & Jefferson Fox 2018

Palm oil’s bad neighbor

In the decade since 2003, rubber investment in Mainland Southeast Asia (also known as the Mekong region) exceeded even that of palm oil. With both commodities, the upsurge in industrial plantation production has been plagued with social and environmental issues.

In the case of palm oil, these issues have gained widespread public exposure since the middle of the last decade due to successful campaigns to expose palm oil’s dark secrets. Campaigning has led to action across the industry from adoption of ‘No Deforestation, No Exploitation’ policies to a plethora of industry and multi-stakeholder efforts to resolve palm oil’s sustainability issues at scale. But the problems in the rubber sector have gone relatively unnoticed until recently, and has thus far the industry has done little to change its behavior.

The problems associated with industrial rubber production and processing are multiple, and severe. Problems plaguing the sector range from massive deforestation, to widespread land-grabbing and associated human rights abuses, to the destruction of huge swathes of endangered species’ critical habitats, contaminating groundwater and aggravating climate change. The list goes on.

Initiatives such as the International Rubber Study Group’s Sustainable Natural Rubber initiative (SNRi) have failed to make much of a dent in rubber’s sustainability footprint, and have largely excluded critical stakeholders, such as NGOs. Furthermore, the fact that natural rubber is less ubiquitous in consumer items than palm oil means that the sector has been able to fly relatively under the public radar. But now all of that is changing.

Reasons for optimism: from recognition, to response, to reaction

With any industry troubled by environmental, social or human rights issues, change does not necessarily happen overnight. In our experience, there is often a learning-to-action curve that moves along a trajectory from ignoring the problem, to angry denial, to grudging recognition, to engagement, and eventually to genuine response and action.

With some industries, this trajectory follows a painfully shallow curve that can drag out each phase for years. Examples of this include the oil and gas extractives sector, as well as the agrochemical, commercial seed, and meat production industries. Not surprisingly, these industries tend to have the worst image in the public eye.

In the case of the rubber sector, however, Mighty Earth is encouraged by signs that the industry is accelerating quickly along this trajectory. From a situation in March 2016, when not a single tire or rubber company had a sustainable natural rubber procurement policy, three years later we have seen nine of the world’s leading tire brands develop and adopt such a policy. Several of the world’s largest rubber companies have done likewise.

Rather than ignoring or denying the issues, companies in the tire and rubber sectors are engaging with us, paying careful attention to our research in the Mekong region and West Africa, seeking to understand the issues, and looking to take real action. And at this year’s World Rubber Summit, sustainability is high on the agenda. It appears the natural rubber industry is listening, and willing to change.

The Global Platform: a springboard for change?

Yet despite recent progress, a huge amount remains to be done. The social and environmental problems in the natural rubber sector are systemic, and won’t be resolved simply by engaging on a company-by-company basis.

That’s why Mighty Earth has decided to become a Founding Member of the new Global Platform on Sustainable Natural Rubber (GPSNR). The Platform has been set up to enable multiple stakeholders in the rubber sector to collectively develop strategies for tackling critical social and environmental issues. This will involve rubber producers, tire companies, car manufacturers farmer representatives, and NGOs working collaboratively to devise solutions.

This is, for sure, a bold experiment, and the launch of the GPSNR has not been without teething issues. During the Platform’s inception, we had to fight hard to ensure that the governance structure provided civil society with an equal seat at the table and voice in decision-making. For many of the companies involved, it will be their first time working in a multi-stakeholder body alongside NGOs. It’s fair to say that some may still be a bit nervous!

However, despite these teething issues, we believe the Platform has the potential to be a springboard for transformative change in the rubber industry. Alongside our fellow NGO founding members, we want to work with companies across the natural rubber value chain to quickly address the sustainability issues facing the industry, monitor progress of implementation of policies already in place, and start changing practices on the ground.

Companies across the rubber value chain increasingly understand their wider responsibilities. Now is the time for them to use the Platform to turn that understanding into action.