Action on AMR Can’t Wait

The CDC estimates at least 2 million people in the US are infected with resistant bacteria each year, and 23,000 people die from those infections. This isn’t a crisis to worry about someday—it’s happening now, and without action, the frequency and severity of AMR will only get worse.

Antimicrobial resistance is an existential threat to modern health care. It has been since shortly after penicillin was discovered. Alexander Fleming had his eureka moment in 1928. By 1940 bacteria were already exhibiting resistance to the drug.

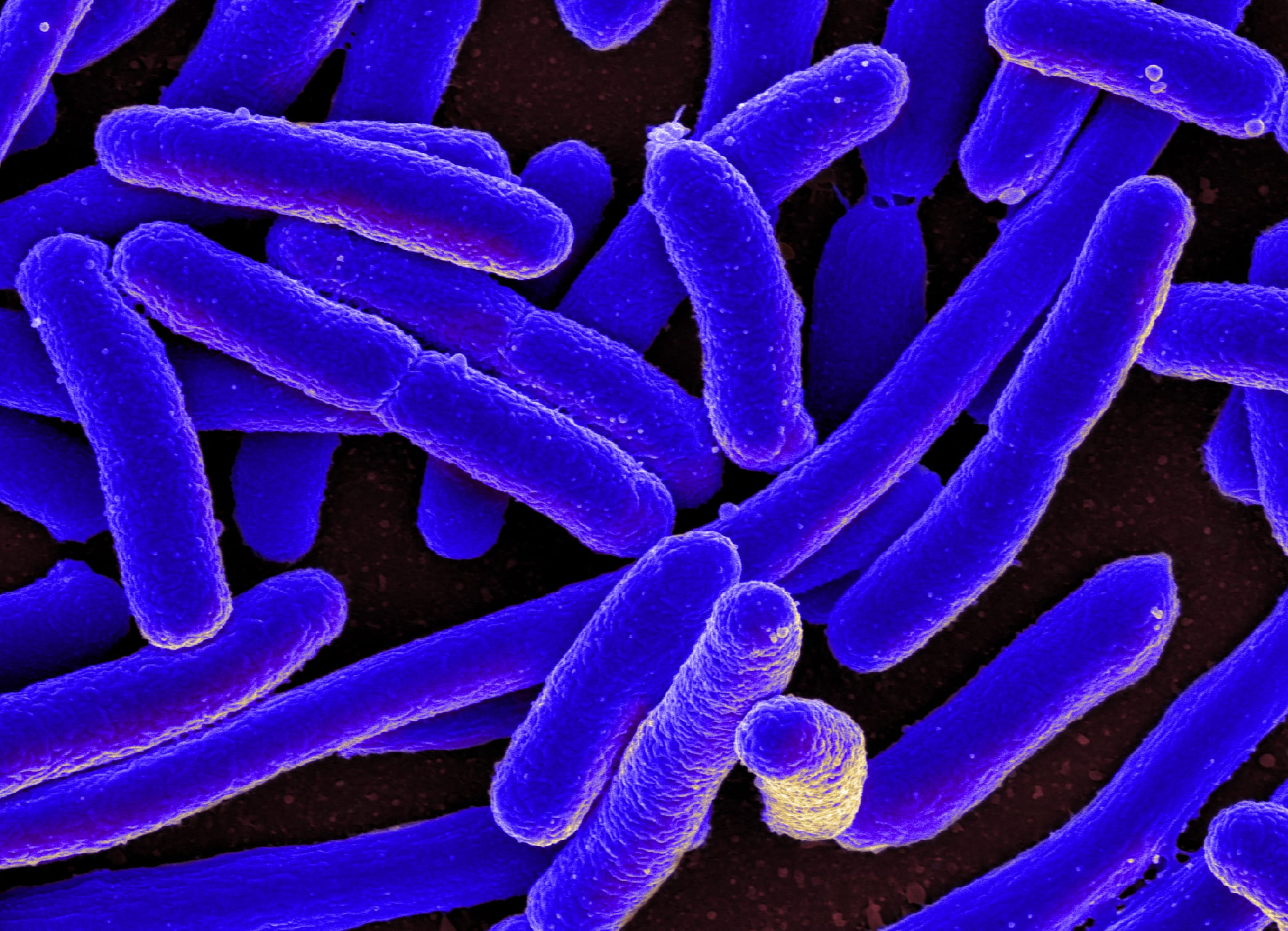

The development of superbugs is evolution we can track in real time. When bacteria come into contact with an antibiotic, most are killed off. But some bacteria survive and develop resistance to that antibiotic, like the microbial version of a flu shot. Fighting these stronger bacteria with the same antibiotic as before won’t be as effective. After enough mutations, a strain completely resistant to that antibiotic—a superbug—could emerge and pass its immunity on to others.

The Evolution of Bacteria on a “Mega-Plate” Petri Dish (Kishony Lab)

Thankfully, people are speaking up. Last year, President Obama introduced the National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and laid out clear goals for our country to fight back the threat of AMR. In September 2016, the UN will host a High-Level Meeting on the issue. From health care professionals to animal rights activists, people are advocating against the practices that exacerbate AMR, like over-prescription, the lack of research into new alternatives, and misuse in livestock. Too many people are taking antibiotics incorrectly or unnecessarily. For too long, pharmaceutical companies have failed to develop new antibiotics, or other alternatives to fighting bacterial infections. And too many farms rely on antibiotics not to heal their keep, but to fatten them up before they go to market.

Polluting manufacturers, however, have flown relatively under the radar in attempts to address the AMR crisis. Waxman Strategies and Changing Markets have identified factory locations primarily in India and China that are linked to massive environmental degradation in the form of pharmaceutical pollution. Independent studies of regions in India, Pakistan, South Korea and Taiwan have found extremely high concentrations of antibiotics (at times surpassing their maximal therapeutic concentrations) in water sources downstream of antibiotic manufacturers. There are also numerous examples of manufacturers that have been sanctioned for environmental malfeasance, yet continue to produce antibiotics for a mass market without proper waste disposal methods in place.

The effects of this contamination are already public health crises in the factories’ locales, effectively poisoning local populations. In the context of antimicrobial resistance, however, this local injustice is also an international one. High concentrations of antibiotics released into the environment from factories create reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance. The impact is similar to that of human and animal waste, but without having been diluted by the digestive process. Superbugs, cultivated in China and India by careless waste disposal and lack of oversight, can then be exported worldwide.

We need action on all of these issues—discovery, over-prescription, misuse in livestock and pollution—to keep the devastating effects of AMR at bay. With any contributor to AMR out there, the efficacy of antibiotics is threatened, and with it modern medicine.